There are certain colours we associate with certain brands. Is this because they’ve used them in their marketing for so long that it’s become memorable? Or, is it a case of these colours actually belong to the brands? We’ll take a deeper look into the idea of trademarking colour schemes.

What are trademarks?

“A trademark is any word, name, symbol, or design, or any combination thereof, used in commerce to identify and distinguish the goods of one manufacturer or seller from those of another and to indicate the source of the goods.” – the Lanham Act. Colours aren’t always included within the definition of trademarks, however that doesn’t mean it can’t stretch to them. After all, if the concept of a trademark is something belonging to an individual or company, then can’t a colour also follow this rule?

Alternatively though, you could argue, trademarks should only apply to anything you create for yourself. You’re not creating a colour, right? Even throwing various shades or tones out there isn’t creating the colour itself. So, where do we draw the line? In fact, colours were once banned from being trademarked. But, in 1995 these rules were altered. Meaning, colour combinations could be trademarked, but only if they were part of a product, package or service. Therefore, you can’t just trademark pink because you like the colour. Nor can you trademark an entire colour as such, rather shades and tones.

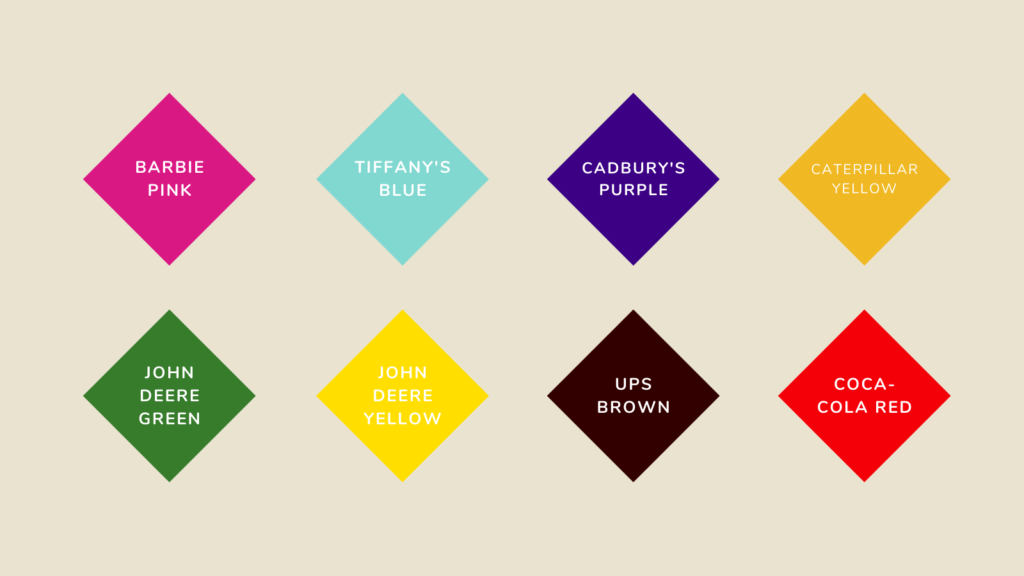

Trademarked colours

In the image above, you’ll see a variety of protected colours. These are specific shades, and there can be repercussions if you’re caught using these for your own marketing and advertising. For the purpose of sharing trademarked colours, we can provide the colour codes. These are as follows; Barbie Pink (Pantone 219C | #DA1884), Tiffany’s Blue (Pantone 1837 | #81D8D0), Cadbury’s Purple (Pantone 2685C | #3B0084), Caterpillar Yellow (Pantone 1235 C | #F0B823), John Deere Green (Pantone 364C | #367C2B), John Deere Yellow (Pantone 109C | #FFDE00), UPS Brown (Pantone 0607298 | #330000) & Coca-Cola Red (Pantone 1788 C | #F40009).

To mark a colour, you’ll need to be able to provide evidence that they have a second meaning. This means, only colours which have a connection to a brand or service are able to be claimed. You cannot trademark a colour because you think it fits your brand. Colours must offer more than a description to your brand. Coca-Cola for example, had no issue trademarking their red colour, because when people see it, they instantly think of their brand. The connection is there, and it offers the company the secondary meaning. It becomes more than just a colour, it’s a feeling and emotion. Associating a colour with a brand enables them to claim it as theirs.

How can you prove secondary meaning?

Unfortunately, it will take a lot more than several of your consumers arguing your case. General Mills who own the much known and loved cereal Cheerios, have previously been denied protection for their yellow colour choice. They have been using the same shade of yellow since 1945 and wanted for it to be trademarked, so it couldn’t be used elsewhere. A well known brand, across the world – seems easy for them to claim the colour, right?

However, it wasn’t so easy. In fact, they weren’t successful in their efforts to secure the colour. It seems to have more chance of claiming a colour, you need to pick something that isn’t as widely used. Arguably, Cheerios yellow colour, isn’t niche enough. Secondary meaning is usually best portrayed through advertising. The colour itself should be used within all adverts. Consumer surveys can help too. By supplying a consumer report showing your audience largely think of your brand or product when seeing a certain colour, you may be able to back up your point.

How can a colour be trademarked?

Certain colours may spark images of specific brands or companies. However, they don’t own the entire colour. As mentioned previously, they’ll own certain tones or shades within the colour spectrum. You may think of Tiffany Blue and be able to picture the shade. However, courts will need more specific processes to determine the exact shade. The Pantone Matching System is an ink matching technique which consists of 1,114 colours. Colours can be mixed and various tones and shades produced. Each shade, or tone will have its own number.

Depending on the shade of a colour mark, will depend on the amount of protection it can receive. For example, if a shade has 10 numbers either side of the main target colour, it’s less protected than those will far fewer. The main target colour will indicate red, blue, green etc, whereas the surrounding numbers will determine the tones and shades. The Pantone Matching System will have specific codes for each trademarked colour. Therefore, it is easy to see if a company has been using a colour they shouldn’t be.

Should you trademark your colour scheme?

As a general rule, you should aim to trademark anything that is of value to yourself or your company. However, bear in mind if you’re new to the industry, you’ll struggle to claim your colour of choice. Not only that, but if you at any stage change your colour scheme, you’ll need to ensure you never move away from the specific colours claimed. Typically, it’s suggested to not aim to trademark any colour unless you have to. Trademarking a colour isn’t offering too much protection over your company. It protects the colour, but not your brand, remember.

It’s better to aim to trademark names or products that help identify your brand. After all, it’s likely these are the things you’ll be remembered for, rather than a particular shade or tone. Trademarking just a colour doesn’t offer your brand security over your ideas or products. As you’re also only marking one particular shade within the Pantone Matching System, you aren’t making your company known for the colour Red or Blue, instead a particular shade. This therefore doesn’t prevent your competition from using a shade that’s almost identical to your trademarked one.

However, with all this being said, for some companies or brands it’s crucial to their work. A particular colour might be the unique selling point (USP) or a product they offer. For example, all Tiffany products have the same colour blue packaging. Likewise, Christian Louboutin high heeled women’s shoes have the distinct red soles. This is a fundamental part of their design and always has been. It is who they are and therefore wanting to trademark that particular colour makes perfect sense. Yes, their rivals can copy the idea, but they’re known for that shade, and it speaks for them.